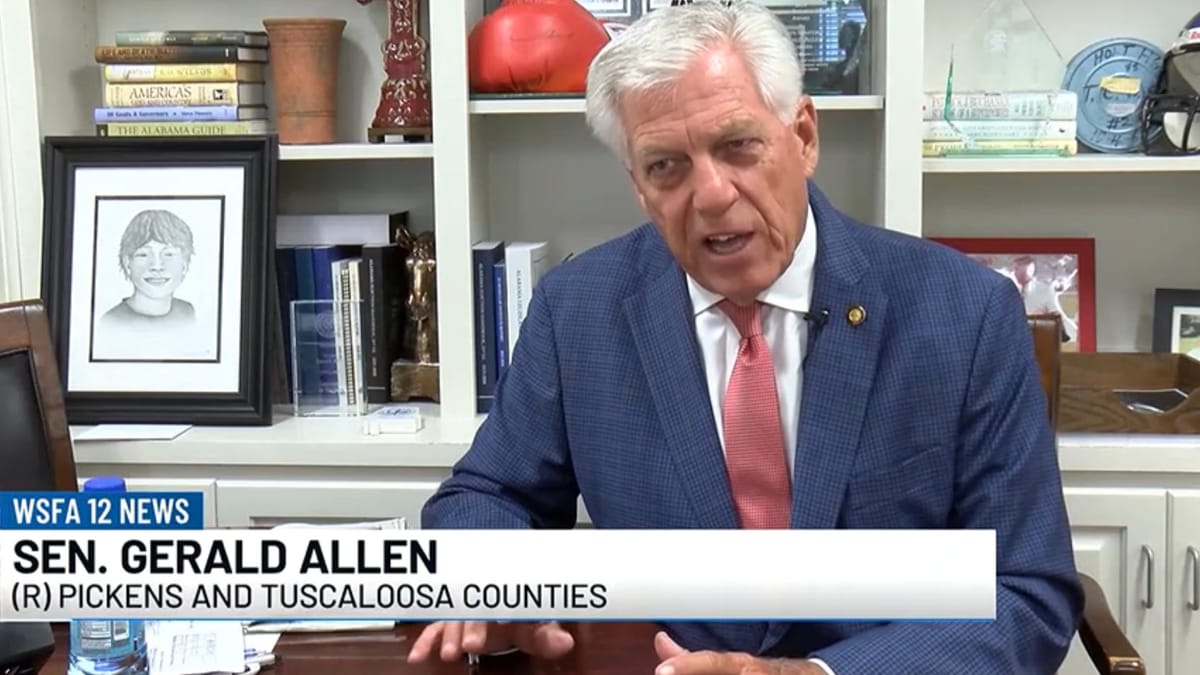

Alabama Senator Gerald Allen Moves to Extend Smokefree Rule to Vaping

Pre-filed SB9 extends smoking ban to vapes, but purported harm may be based on junk science

Alabama State Senator Gerald Allen (R‑Tuscaloosa) is taking aim at vaping in public places.

Allen has pre‑filed Senate Bill 9 (SB9), that will amend the Alabama Clean Indoor Air Act. The bill would officially treat vaping—officially defined as use of an “electronic nicotine delivery system”—just like smoking, effectively banning it inside restaurants, malls and sports venues, as reported by WSFA.

“That needs to be a priority of ours to make sure the citizens know that when they’re going into a public place, they cannot vape,” Allen said.

Alabama already restricts vape sales, especially those targeting youths. Just last legislative session, Alabama passed House Bill 8 (HB8/Act 2025‑403), a sweeping reform on vape sales and access. It took effect June 1, 2025. HB8 bans the sales of most flavored e-cigs in convenience stores (restricting them to licensed specialty vape shops), imposes a new $1,000 Specialty Retailer Permit on those shops (instead of the $150 standard ABC Tobacco Permit), limits their sales to 21 and up, bans vending machine sales of vape and tobacco products, and requires school boards to adopt anti-vaping policies based on a State Board of Education model policy.

The Alabama Department of Public Health warns that even second‑hand vaping can harm the lungs, heart and breathing. “Just like cigarettes have second‑hand smoke, vapes also have second‑hand aerosol, which contain a mixture of nicotine, ultra‑fine particles and other potentially harmful substances,” said Tracie Cole, Cessation Program Manager at ADPH.

Allen added: “I challenge the citizens to google vaping and look for themselves. It’s a very serious issue, and that’s why I have this important bill to go in and add this to the code, to add this to state law.”

While smoking bans are often defended as essential public health measures, recent evidence suggests the dangers of secondhand smoke—especially in short-term or casual exposure—may have been overstated. The Helena, Montana study from 2003, which claimed a dramatic 60% drop in heart attacks after a local smoking ban, was widely cited at the time. However, follow-up research with larger populations and more rigorous methods failed to replicate such results. Studies in England, Italy, and elsewhere found only modest or no reductions in heart attacks after similar bans. A comprehensive 2010 RAND Corporation analysis involving over 15,000 data comparisons found:

“no evidence that legislated U.S. smoking bans were associated with short-term reductions in hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction or other diseases in the elderly, children or working age adults.”

Even some of the researchers who once reported health improvements later admitted their earlier findings may have been skewed by small sample sizes and publication bias. These results raise questions about whether sweeping bans—especially those that now include vaping or outdoor areas—are truly justified by the data or driven more by social preferences and stigma than by measurable health risks. (For a review of this issue, see We Used Terrible Science to Justify Smoking Bans, Jacob Grier, Slate, 2017.)

Alabama’s new push to restrict vaping in public spaces brings aligns with States like Florida and Georgia, but still lags behind others like Arkansas and Louisiana when it comes to indoor vaping bans. Arkansas, for example, already includes vaping under its Statewide Clean Indoor Air Act, banning use of e-cigarettes in most public places. Louisiana passed a similar law in 2023, aligning vaping regulations with smoking bans in workplaces, restaurants, and public buildings. These laws generally treat vaping and smoking the same under the law, reinforcing the idea that secondhand vapor carries public health risks similar to secondhand smoke.

Tennessee and Mississippi, by contrast, have more limited restrictions. While both States regulate sales and youth access, they do not have comprehensive Statewide bans on vaping in indoor public spaces. Instead, they leave such decisions largely up to local governments or individual business policies. Florida made headlines in 2020 when voters approved a constitutional amendment banning vaping in enclosed indoor workplaces, signaling a shift in public opinion even in States known for lighter-touch regulations. If Alabama’s Senate Bill 9 becomes law, the State would join a growing list of Southern States responding to health officials’ warnings about secondhand aerosol exposure and the rise of vaping, especially among young adults—but this could be largely based on flawed, junk science.

If passed, Senate Bill 9 would take effect October 1, 2026.