Let Alabamians Help Injured Wildlife Without Fear

The Alabama Good Samaritan Wildlife Rehabilitation Act—because good faith should not be a crime—Guest Opinion by Alicia Haggermaker

Guest Opinion by Alicia Haggermaker

Earlier this year in Huntsville, my husband came home to find a black vulture with a broken wing sitting on our porch.

We did what most Alabamians would do. We tried to help.

We provided food and shelter and started calling for guidance. What followed was hours of phone calls, referrals, and conflicting instructions. Eventually, we were given two options: one veterinarian in Huntsville that was already closed, and one in Guntersville that would also have been closed by the time we could physically get there.

There are only a handful of raptor-capable facilities in the entire state. They are hours apart, frequently full, and often inaccessible outside narrow business hours. Yet the responsibility for transport — along with legal risk — is routinely pushed onto private citizens, without equipment, authority, or any guarantee the animal will even be accepted.

After hours lost to delay and uncertainty, the vulture moved on to a neighboring property. Later, someone else did manage to get help — but by then, it was too late. The bird died.

That outcome didn’t happen because people didn’t care.

It happened because the system made timely help nearly impossible.

And this was not an isolated incident.

A friend later shared a nearly identical experience involving another injured vulture in North Alabama. In that case, a woman with ties to raptor rescue cleared transport in advance and drove the bird to Birmingham herself — only to be turned away on arrival. Same region. Same delays. Same result.

These stories aren’t about reckless people interfering with wildlife. They are about ordinary citizens trying to do the right thing and being blocked by ambiguity, fear, and over-restriction.

That is exactly the gap the Alabama Good Samaritan Wildlife Rehabilitation Act is designed to close.

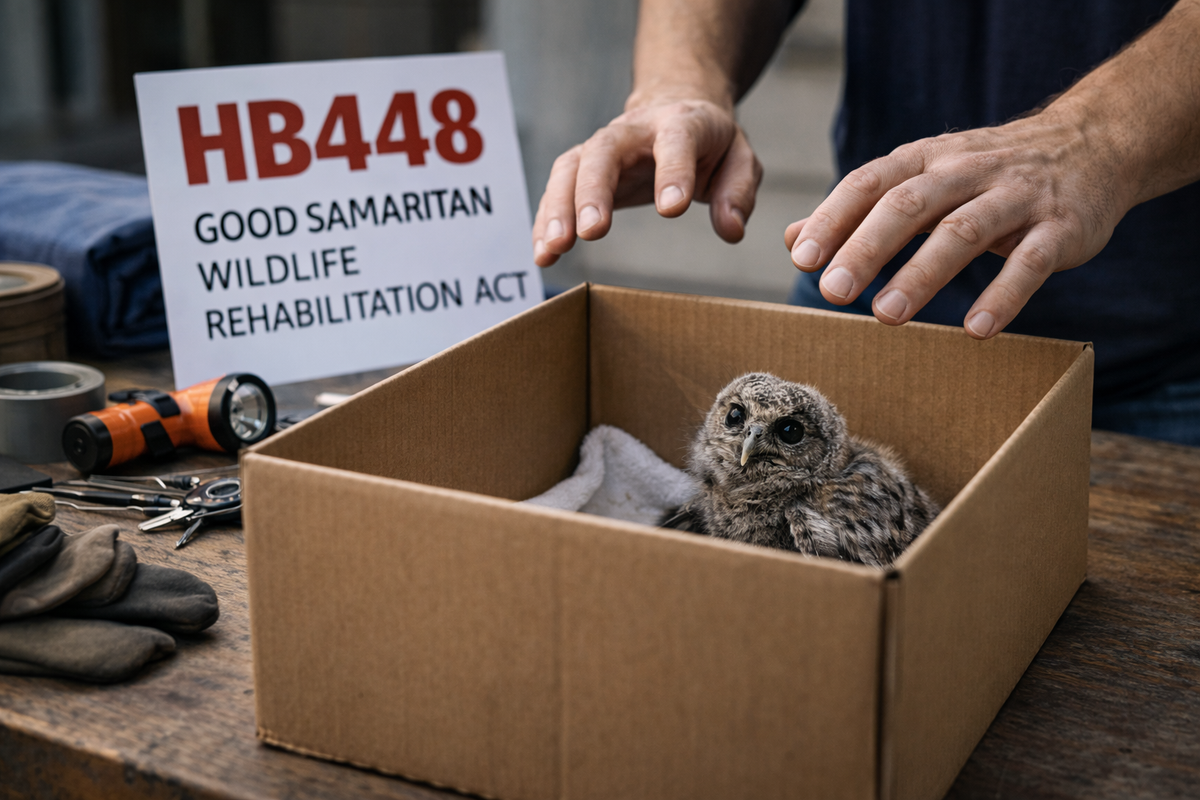

Introduced by State Representative Ben Harrison (R–Elkmont) in the 2025 legislative session as HB448, the bill would allow individuals to provide good-faith, temporary care to injured or orphaned wildlife that are not federally protected or endangered. The bill is narrowly written. It does not override veterinary practice laws or animal cruelty statutes. It simply clarifies that stabilizing an animal and trying to return it to the wild should not make someone a criminal.

This reform is long overdue.

Alabama has gone from more than 100 licensed wildlife rehabilitators in 2013 to just five today, following state restrictions that go beyond federal guidance. Under current rules, residents are often told to “let nature take its course,” even when injuries are clearly caused by cars, development, poisoning, or other human activity. Compassionate Alabamians who try to help risk confiscation of the animal — and immediate euthanasia.

That approach does not reflect Alabama values, and it does not reflect public opinion.

A February 2025 statewide poll found that 66% of Alabamians support legislation allowing citizens to care for injured or orphaned wildlife, with only 14% opposed. More than 12,000 people have signed petitions calling for reform. Wildlife rehabilitation organizations across the state — including the Alabama Wildlife Conservation and Rehabilitation Society, North Alabama Wildlife Rehabilitators, and Alabama NEEDS Wildlife Rehabbers — support the bill.

HB448 passed the House Agriculture and Forestry Committee on a 9–3 vote but was not considered by the full House, dying in the 2025 session.

At its core, this bill rests on a simple principle: when systems are stretched thin, people should be allowed to help — not punished for trying.

Good Samaritan protections already exist in many areas of life, from medical emergencies to disaster response, because we understand that delay can be fatal. Wildlife emergencies are no different. Animals deteriorate quickly from stress, injury, and exposure. When help is blocked by fear of enforcement or unclear authority, suffering increases — and outcomes worsen.

The Good Samaritan Wildlife Rehabilitation Act doesn’t ask the state to do more.

It asks the state to stop preventing others from doing what the system no longer can.

This is about compassion, common sense, and letting people act in good faith when time matters. It is about aligning the law with reality — and with the values most Alabamians already hold.

The Legislature should pass the Good Samaritan Wildlife Rehabilitation Act, and the Governor should sign it.

Because when helping becomes illegal, doing nothing becomes the default — and animals pay the price.

Editor’s note: the text of the Good Samaritan Wildlife Rehabilitation Act, as introduced in the 2025 session as HB448, may be found at THIS LINK. At press time, there was no record on ALISON of a comparable bill being pre-filed for the 2026 session, which begins January 13, 2026.

Alicia Boothe Haggermaker is a lifelong resident of Huntsville, Alabama, and a dedicated advocate for health freedom. For more than a decade, she has worked to educate the public and policymakers on issues of medical choice and public transparency. In January 2020, she organized a delegation of physicians and health freedom advocates to Montgomery, contributing to the initial draft of legislation that became SB267.

Opinions do not reflect the views and opinions of ALPolitics.com. ALPolitics.com makes no claims nor assumes any responsibility for the information and opinions expressed above.