Pentagon Press Corps Walks Out

New media policy creates a First Amendment flashpoint

Dozens of Pentagon reporters handed in their building badges on Wednesday rather than agree to a new War Department media policy that journalists say would hand the government veto power over routine reporting. The move marks a sharp break with decades of in-house coverage and raises immediate First Amendment questions about the public’s right to know what its military is doing.

Under the memorandum issued this fall, Pentagon credential holders were asked to acknowledge a set of requirements that go beyond long-standing newsroom etiquette. The changes would, among other things, limit reporters’ access to many parts of the building without a Pentagon escort, bar solicitation or publication of information the department says is not authorized for release, and create a paperwork trail that critics warn could make reporters vulnerable to disciplinary or legal action. The policy also asks outlets to affirm that disclosure of certain information “could harm U.S. national security,” language legal experts say could be used against journalists later.

Secretary of War Hegseth described the new policy in a post as:

Pentagon access is a privilege, not a right. So, here is @DeptofWar press credentialing FOR DUMMIES:

Press no longer roams free

Press must wear visible badge

Credentialed press no longer permitted to solicit criminal acts

DONE. Pentagon now has same rules as every U.S military installation

The new policy differs from long-standing practice in two key ways. First, reporters who have long worked inside the building with relatively free movement would now face escorted travel and limits on whom they may interview inside the Pentagon. Second—and most disturbing—the memorandum asks reporters and organizations to accept constraints on what may be published if the Department says the material was not authorized, a step reporters call a form of prior restraint—a blatant violation of the First Amendment. Under the previous practice, reporters relied on source interviews and editorial judgment without department sign-off.

The most problematic section of the new policy—requiring the publication of only “authorized” material—reads as follows (emphasis added, from memo below, p. 3):

Public Release of DoW Information and the Protection of Classified National Security Information and Controlled Unclassified Information

DoW remains committed to transparency to promote accountability and public trust.

However, DoW information must be approved for public release by an appropriate authorizing official before it is released, even if it is unclassified. The Department of War must safeguard classified national security information (CNSI), in accordance with Executive Order 13526 and the Atomic Energy Act, and information designated as controlled unclassified information (CUI), in accordance with Executive Order 13556.

Only authorized persons who have received favorable determinations of eligibility for access, signed approved non-disclosure agreements, and have a need-to-know may be granted access to CNSI. DoW may only provide CUI to individuals when there is a lawful governmental purpose for doing so.

Unauthorized disclosure of CNSI or CUI poses a security risk that could damage the national security of the United States and place DoW personnel in jeopardy.

Faced with that choice, most of the Pentagon press corps chose independence. Major outlets that publicly declined to sign included The New York Times, The Associated Press, Reuters, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, NBC, ABC, CBS, Fox News, PBS and several leading online outlets. News organizations said they would continue to cover the War Department from outside the building rather than accept a policy they view as unconstitutional and chilling.

By contrast, One America News Network (OANN) is the only outlet widely reported to have signed the Department’s document. Reuters and other outlets cited an OANN statement saying the network had “signed the document” after review by counsel. The Pentagon has not released a public list of signatories.

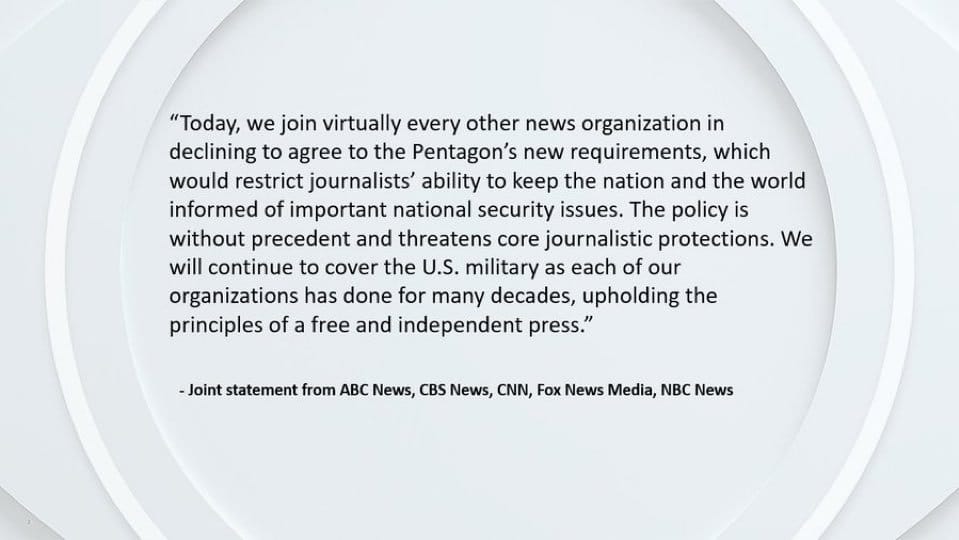

In an unusual show of unity, the five major broadcast networks and three cable giants issued a joint statement saying in part: “Today, we join virtually every other news organization in declining to agree to the Pentagon’s new requirements, which would restrict journalists’ ability to keep the nation and the world informed of important national security issues.” That statement framed the decision as a defense of core newsgathering rights.

Veteran reporters on the beat voiced the same point bluntly. Eric Schmitt of The New York Times wrote that after 35 years covering the Pentagon he would “turn in my building badge today rather than submit to DoW’ vague new policies that restrict my right to engage in ordinary and legal news gathering.” Nancy Youssef, a longtime Pentagon correspondent, said she was “sad, but proud” of the press corps for sticking together and vowed to keep reporting. Tara Copp of The Washington Post was photographed saving newsroom plaques as colleagues packed up — a small, human detail that underscored how sudden the rupture felt.

Legal scholars and press groups described the policy as an unprecedented squeeze. For decades, courts have made clear that prior restraint—government approval before publication—is presumptively unconstitutional. Requiring reporters to acknowledge rules that curb ordinary reporting or to treat the Pentagon as a gatekeeper for what may be published risks creating exactly that restraint, critics say. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and the Pentagon Press Association warned the revised rule is incompatible with the press’s role of holding power to account.

The policy was advanced under War Secretary Pete Hegseth—himself a former cable commentator—and arrived amid repeated complaints from senior officials about “disruptive” coverage. Critics argue the policy is about control, not national security. The Department insists the rules are “common sense” measures meant to protect sensitive information and ensure consistent messaging. That answer has not satisfied outlets that say an independent press is the better guardian of security and truth.

With the badges returned and workspaces emptied, Pentagon reporting will move outside—to interviews, leaks, FOIA, and court action when necessary. Coverage will continue, even if it is slower and more difficult for journalists. Editors and news executives warn that the public will lose the immediacy and institutional memory that come from having reporters on the inside. For now, the standoff is a clear test: will the administration press its new rules? And, will the courts or Congress push back to defend a free press that can scrutinize America’s use of force?

ALPolitics.com would also like to ask one additional question:

Does anyone else remember the Pentagon Papers?

The full memo detailing the Pentagon’s new media policy is available HERE.