Promoting Infrastructure in Early America

Guest Opinion by Justice Will Sellers

Guest Opinion by Justice Will Sellers

Two hundred years ago, the Erie Canal was finally completed, and to celebrate the achievement the Governor of New York and other local elected officials engaged in a progressive celebration.

They sailed from Lake Erie to New York Harbor with stops at communities along the way. It was like a 10-day tailgate with parties, speeches and all-day public celebrations, and it culminated in a ceremonial "wedding of the waters" when water from Lake Erie was poured into New York Harbor.

The completion of the canal was hardly inevitable. While not the first, it was certainly one of the major regional economic development activities undertaken by any government in America, and while there were some supporters for the project, their numbers were initially small.

Like most large, visionary projects there is always the first "idea man" who sees the potential and possibility and then sets out to make the vision real. In this case, the man was flour merchant, Jesse Hawley, who realized, while in debtor's prison, that if the farmlands in the western portions of his state could access an Atlantic port, they would have new markets for their produce.

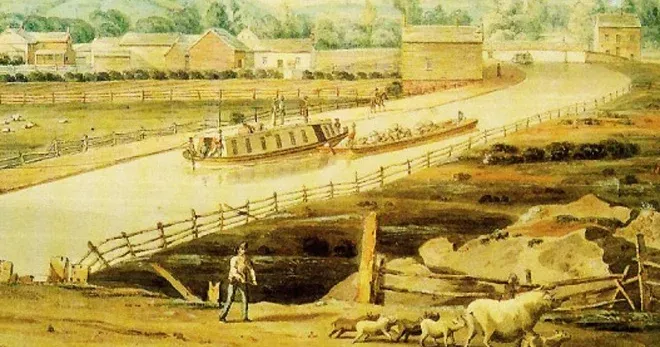

Transportation was a challenge in the early days of America. Natural rivers provided the most efficient means for trade, but interior sections of the country, where rivers were not abundant, were limited to ground transportation. Roads were scarce and not well maintained, and transporting goods required pack animals that could travel only short distances. Depending on the topography, pack animals could cover a little more than 20-25 miles a day, as opposed to river barges, which could move significant quantities of goods faster, farther, and cheaper. Pack animals simply could not carry the same weight with the same efficiencies.

Engineers in Europe had successfully built canals to solve this problem. In America, canals of short distances using small locks had been competently constructed, but the expense of larger canals was too great for private financing, so proponents of the first stages of the Erie Canal attempted to get the State of New York to bankroll the undertaking. Initially, the legislation went nowhere. When the idea was suggested to President Thomas Jefferson, he rejected the proposal as sheer madness.

Even with his creative mind, Jefferson could not envision a man-made public river spanning more than 360 miles that required cutting through rocks, clearing trees, and excavating uneven terrain. To make matters worse, there were no civil engineers in America to design the placement of locks up and down this expanse, yet Hawley refused to give up. With grand visions but little financing, he lobbied for the federal government to support various infrastructure projects, which would include his Erie Canal.

Even though the bill had wide support and passed Congress, President James Madison vetoed the measure on the grounds that it was unconstitutional as he did not believe the Constitution allowed the funding of infrastructure projects. He believed those were best left to the states.

Hawley then worked to enlist the support of New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, who realized this type of canal would link the western and eastern portion of his state to open up new trade routes. Despite opposition, Clinton became the champion of the project and worked to have the state issue $7 million — more than $200 million today — in bonds to finance the canal. The project would be derided as "Clinton's ditch," which initially seemed accurate given the struggles, setbacks and pit falls that occurred as the initial 15 miles of canal took more than two years to complete.

But Clinton persisted and did all he could to support the project. The canal would be the second longest in the world, and even today, something of this enormity would be considered an enormous undertaking. The magnitude of the project is even more astounding as there were only animals and human labor to cut through rock, fell trees, and dig navigable ditches. Construction equipment was limited, but with each obstacle, American creativity, if not ingenuity, succeeded. In fact, the construction of the canal created new means and methods of construction techniques.

As the project moved forward and as each section was opened and utilized for trade, those along the route realized the communal benefits of the project. Once they saw the ease of moving goods along the canal, the possibilities became abundantly clear. Thomas Jefferson even came to embrace the project and the visionary wisdom of Gov. Clinton.

After eight years of hard work, the canal was completed in 1825 . While the initial intent was to open up trade between Lake Erie and New York, the unintended consequences were even more promising in the growth and prosperity of communities all along the canal. In addition to the ease of transporting goods, new businesses sprang up along the canal route providing even more goods to ship on the canal. The canal created a new industry. Tourism flourished as individuals and families curious about the canal explored the interior of the country staying at hotels and dining at restaurants along the way.

The project exceeded all expectations. In its first year of operation, the canal generated more than $1 million of revenue, which allowed the bonds to be paid off early. Transportation costs decreased more than 75% and, in some instances, even more. Tariffs generated from goods shipped and received from New York Harbor became one of the most significant revenue streams for the federal government. Perishable goods could now be shipped quickly, so seaboard residents had fresh produce and interior residents had edible seafood.

The canal was among the main reasons New York City prospered. In fact, New York's port activity caused other seaboard cities to consider similar canals to open up their interior in the same way to enhance their trade. But New York had a head start and never looked back.

What started out as Clinton's folly became Clinton's success as economic development from the canal increased trade, prosperity, and tax revenues.

Will Sellers is a graduate of Hillsdale College and is an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of Alabama. He is best reached at jws@willsellers.com.

Opinions do not reflect the views and opinions of ALPolitics.com. ALPolitics.com makes no claims nor assumes any responsibility for the information and opinions expressed above.