Supreme Court Leans Toward Limiting Race-Based Redistricting in Louisiana Case

Louisiana v. Callais decision could affect redistricting efforts nationally, especially with regards to Alabama’s Milligan case

The U.S. Supreme Court appears ready to narrow how race can be used in redistricting, as justices heard arguments Wednesday in a Louisiana case that could rewrite a key section of the Voting Rights Act and alter congressional maps across the country.

At issue in Louisiana v. Callais is a map that, after lower-court rulings, added a second majority-Black congressional district in a State where roughly one-third of residents are Black. Black voters and their lawyers argued the State’s earlier map diluted their influence and that creating a second majority-Black seat was a lawful remedy under Section 2. Opponents—a group of voters who describe themselves as “non-African American”—say the new map sorts people by race in a way the Constitution forbids.

After the Supreme Court agreed to rehear the case, Louisiana abandoned defending the map, arguing that the Constitution should not compel racial line-drawing.

Over two hours of questioning, the Court’s conservative majority voiced concern that states like Louisiana are going too far in deliberately creating additional majority-Black districts to satisfy federal voting laws—steps some justices suggested may now violate the Constitution.

The dispute centers on whether Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act—meant to prevent racial vote dilution—can require States to draw majority-minority districts, or whether doing so amounts to unconstitutional racial sorting under the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh signaled skepticism toward ongoing racial balancing. “This court’s cases in a variety of contexts have said that race-based remedies are permissible for a period of time,” he said. “But that they should not be indefinite and should have an end point.”

Louisiana Solicitor General Ben Aguiñaga echoed that frustration, telling the Court the state never wanted to pass its current map. “We never wanted to be here in the first place,” he said. “They have placed states in impossible situations where the only sure demand is more racial discrimination for more decades.”

He added, “The Constitution does not tolerate this system of government-mandated racial balancing.”

The Justice Department took a more moderate view, urging the Court to clarify—not erase—the Section 2 framework. Principal Deputy Solicitor General Hashim Mooppan said plaintiffs should have to show an alternative map that is demonstrably superior and an “objective likelihood” of intentional discrimination. “What’s going on under Gingles now is not actually figuring out whether there’s an unfair effect based on race; it’s figuring out whether there’s an unfair effect based on party,” he said.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett questioned whether that approach would necessarily overturn precedent. “Is there a way to say it’s a clarification of Gingles? I mean, Gingles is a 40-year-old precedent. A big ask to change it.”

Liberal justices pushed back. Justice Sonia Sotomayor accused the administration of trying to “get rid of Section 2,” while Justice Elena Kagan noted that the challengers’ arguments “have been specifically rejected by this court over many decades.”

Outside the courtroom, the case drew national attention after a social media clip of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s comments sparked partisan debate. Breitbart highlighted her analogy comparing the obstacles faced by minority voters to those experienced by people with disabilities—a line that quickly trended online.

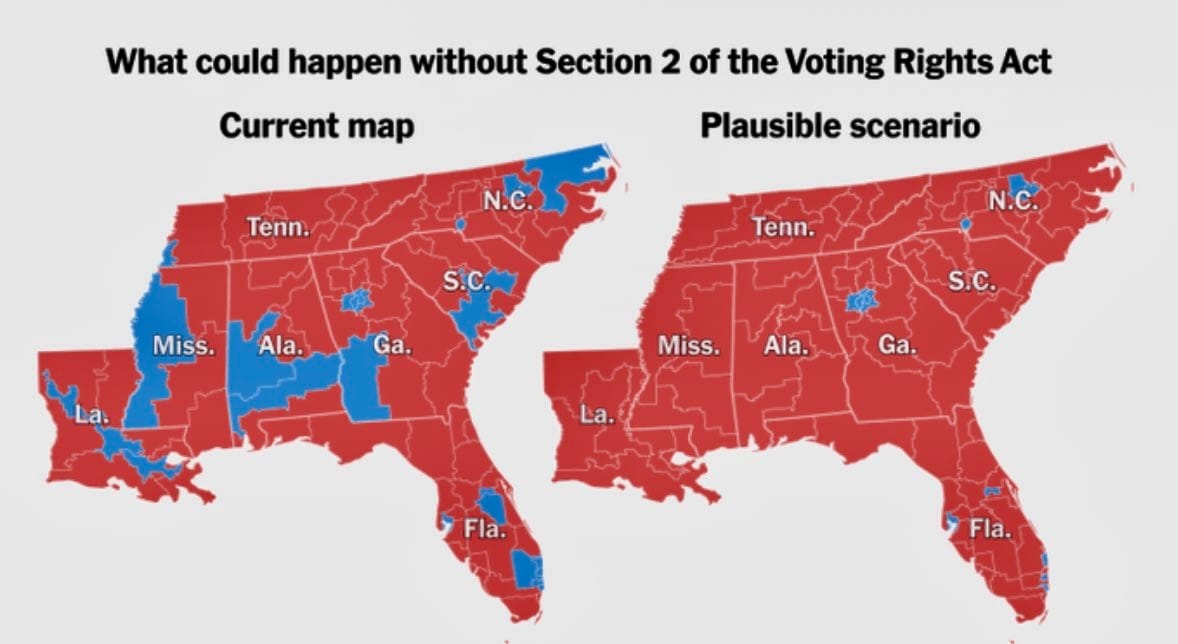

NAACP Legal Defense Fund President Janai Nelson countered that undoing the current framework would erase decades of hard-won gains. “We only have the diversity that we see across the South because of litigation that forced the creation of opportunity districts,” she told the Court. “It would be catastrophic for Section 2 to cease to operate as it does today.”

The outcome in Louisiana v. Callais could also ripple into neighboring Alabama, where the Supreme Court’s 2023 Allen v. Milligan ruling forced lawmakers to draw a second majority-Black district. If the justices now narrow how Section 2 applies or limit the use of race in line-drawing, Alabama’s revised map—and others created under Milligan—could face fresh challenges. A decision restricting race-based remedies would effectively undercut the reasoning behind Milligan and invite States to revisit or even reverse those court-ordered districts.

Anticipating that possibility, the Alabama Republican Party (ALGOP) has filed an amicus brief urging the justices to treat voters as individuals rather than members of racial groups, arguing that Milligan and similar cases “place states in a perpetual cycle of race-based mapmaking.” ALGOP’s amicus brief asks the Court to reject racial classification in districting altogether. “Every voter deserves to be treated as an individual, not as part of a racial or ethnic group,” ALGOP Chair John Wahl said in announcing the brief.

Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry (R) attended the arguments alongside Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.). Landry told The Hill that redistricting is “a political process that should remain in the hands of elected representatives.”

“The more the court gets involved in a legislative process, the more it entangles itself in its own opinions,” he said, urging the justices to bring the matter to a close. “I hope that this is the end of the tracks.”

A decision in Louisiana v. Callais is expected by June 2026. Though unlikely to alter next year’s elections—it would come after Alabama’s May 19 primary—it could reshape congressional maps, and the legal limits on race-conscious redistricting, for years to come.

The official transcript of Wednesday’s arguments before SCOTUS is available HERE.